WORKING ASSETS: Maintaining balance between business and residential land use is key goal

John Bermingham

Province

For gallery owner Svetlana Fouks, Yaletown is a livable, workable community. GERRY KAHRMANM — THE PROVINCE

Over the past 30 years, the city has lost 250 acres of commercial and industrial space in the downtown peninsula to residential use. In the process the region has seen creation of 44,000 new jobs and 26,000 new residents.

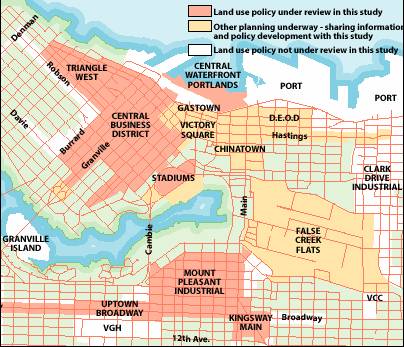

Now, Vancouver city planners are embarking on a 25-year land-use plan to see how much of the remaining core industrial land-base needs to be protected.

“We’ve had tremendous success with new residential development,” said Ronda Howard, senior planner with the city. “Now the challenge is posed by where those trends are leading.”

Howard said there is persistent pressure from residential developers to free up industrial land earmarked for future business growth.

Areas like Gastown, Yaletown, Burrard Slopes and Mount Pleasant are all under pressure from residential development.

And even though the city tried to protect its downtown land-base in 1991 by retaining an office core, surrounding it with condos and shifting industrial land to the central business district’s outskirts, residental high-rise construction has surged beyond all expectations.

Hence, residential values have continued to climb, while commercial values remained static. But businesses pay $5 in property taxes to the city for every $1 by homeowners. So, maintaining a balance between business and residential land use is a key goal for the Metropolitan Core Jobs and Economy Land-Use Plan group.

It will form a 30-member advisory board, drawn from business groups, landowners, developers and transport interests.

The plan’s other goals include:

n Anticipating future growth trends in key economic sectors, such as tourism, manufacturing, recreation, high-tech and retail.

n Creating a land-use plan.

n Clarifying the role of mixed live-work spaces, heritage buildings and commercial space in providing for future jobs.

The group will also study the impacts of increasing conversions of industrial buildings to residential usage, such as in heritage Yaletown — even though last May the city placed a moratorium on those conversions in the downtown core.

The live-work mix is working particularly well in places such as Yaletown where Svetlana Fouks runs a native art gallery which is just five minutes from her home.

“This is one of the most livable and workable communities in North America. It’s one of the reasons [Yaletown] attracts so many to live and work here,” she said.

“This area will survive if it has enough of a balance. If there’s too much residential, then the commercial will suffer,” she said.

“The city knows they have to foster that commercial element.”

Adds David Podmore, president of the Urban Development Institute: “It’s really important to make sure we can achieve a balance between our ability to provide jobs, and accommodate commercial and industrial uses in the city, and balance that with the residential capacity of the city.”

Charles Gauthier, executive director of the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association, says it’s vital to protect the city core’s job-base, set to rise from 150,000 today to 175,000 by 2021.

However, in the past the city has found it “much more politically expedient” to allow industrial land to be used for residential development, adds Coun. Sam Sullivan.

“There’s not as much of a public backlash,” he says. “We’ve had to draw a line in the sand to make sure residential didn’t totally overwhelm the commercial.”

And Dave Park, economist with the Vancouver Board of Trade, says higher residential property values shouldn’t compel conversions of commercial space.

“The principle here is much akin to the Agricultural Land Reserve,” said Park.

“Just because one land-use can bid up the price, doesn’t mean that it makes sense for the community.”

He warns that if the city loses too much industrial land, it will not only have an impact on Vancouver‘s economy, but the provincial economy as well.

GROWTH CLUSTERS

One way of growing business in a densely packed metropolis is through clustering. The Vancouver Economic Development Commission believes sectors such as high-tech, film, tourism and clothing could concentrate in campus-style centres. The biotech sector is already locating at the University of B.C. and Vancouver General Hospital. Clothing firms are linked to Gastown, high-tech firms to Yaletown.

“As most industry sectors develop, their proximity to each other becomes more valuable,” said Ken Veldman, VEDC’s director of business development. Clustering can also work in areas with a high residential build.

© The Vancouver Province 2005