SUSTAINABILITY : Creating a livable city means accepting more density

PETER BIRNIE

Sun

When Vancouver held the Habitat For Humanity conference in 1976, Imelda Marcos defended her dictator husband’s slum-clearance program in the Philippines, Mother Teresa pleaded for the world’s poor, Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau decried “the recklessness we have displayed toward nature” and his wife Margaret demanded “action, not promises” on cleaning up the world’s water supply.

The African National Council of Zimbabwe attacked apartheid in South Africa, the head of the Soviet delegation joined in a walkout led by the Palestine Liberation Organization to protest Israeli settlements on Palestinian land, and legendary architect R. Buckminster Fuller delighted schoolchildren with a positive vision of the future. Not so positive, perhaps, as that of U.S. social scientist Dr. Magoroh Maruyama, who declared at Habitat that 10,000 people could be living in outer space by 1990.

Next year, Vancouver hosts the third World Urban Forum, dubbed Habitat+30, but its focus is likely to be a whole lot narrower than that of the first Habitat. The world’s urban areas face enormous pressures on so many fronts that Habitat+30 must eschew debate on world peace and space colonies to deal with such mundane but vital issues as sewage treatment, transportation, housing, infrastructure and land use.

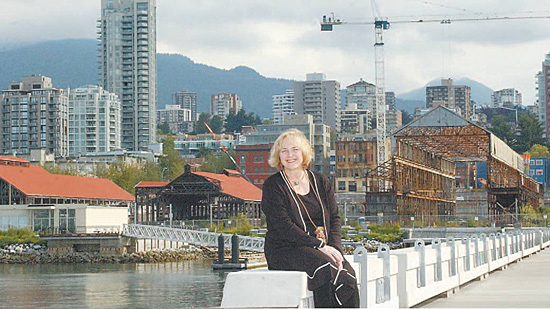

North Vancouver Mayor Barbara Sharp is director of the International Centre on Sustainable Cities. Earlier this month she took part in Financing Smart Growth, an all-day forum at the Hilton Metrotown focused on finding a sustainable balance between business interests and community needs.

Living together better

“We need people to understand,” says Sharp, “that in order to be sustainable we’re going to have to try to learn to live together a little better, be a little more tolerant. It’s all for the greater good, for better-quality air, betterquality water, better management of transportation and more efficient spending of your money.”

North Vancouver is a prime example of the changes being made across the Greater Vancouver Regional District in a bid to channel growth. The SeaBus arrived at Lonsdale Quay in 1977, followed by the market and hotel in 1986, and an initial burst of business interest that saw ICBC relocate there. But it’s only after years of stasis that a genuine sense of momentum has finally hit the neighbourhood. Condo projects are popping up all around Jack Loucks Court — a new park located on Second Street between Lonsdale and Chesterfield — and on the waterfront, the Versatile Shipyards, closed in 1992, are being prepared for major residential and retail development.

“Density is the key to smart growth,” Sharp says. “From the ’50s to the ’80s, much of what was developed at that time was not sustainable. The supply of land is limited and we cannot continue to sprawl.”

The GVRD not only has its head office in Metrotown but was a pioneer in bringing jobs to the neighbourhood when it moved there in 1980. Today, Metrotown has the region’s most complete mix of residential, retail and office uses outside central Vancouver, and GVRD regional development division manager Chris DeMarco says about 30,000 people now live within walking distance of the jobs in Metrotown. It’s something the GVRD also wants to see occur in its other designated regional town centres in Maple Ridge, Surrey, Richmond, New Westminster, Coquitlam, Langley and Lonsdale.

“The town centres are doing pretty well and, by North American standards, very well,” she says. “People are looking for that

lifestyle where they don’t have to drive to get around, and seniors are getting rid of their suburban bungalows to move into town centres. They want to stay relatively close to their friends, but don’t want to have to maintain a big house.”

That and a booming real-estate market are helping buoy denser residential development, “and on the retail side,” Demarco adds, “we’re quite lucky that all the centres have a strong historic retail function.”

In New Westminster, retail growth is a key concern of Tim Whitehead, the city’s director of development services. On the residential side he’s enjoying the renewed interest that will see, among other projects, five towers, each over 30 storeys, along the Fraser River.

“It’s not just we the bureaucrats who are saying New West is the next to develop,” Whitehead says. “There are no more waterfront development sites left in Vancouver, so the Vancouver market is now looking our way.”

But no amount of residential redevelopment can yet help Columbia Street, which was once a major shopping hub and home to a number of department stores but is now down at heel and blighted by truck traffic. Whitehead wants the trucks shifted so they’re out of sight along the railway tracks, with much better pedestrian links between Columbia and the waterfront.

Then, he adds, “a downtown such as this, with its historical resources, needs to redefine itself as a niche market. There’s no sense saying that we can compete with the major outlying malls or the Wal-Marts of the world, but retailers here can define themselves as a niche market of specialty shops attractive to people who want to come downtown, as much for a recreational and entertainment experience as for a shopping experience.”

Transit challenge

Richmond faces an even more daunting obstacle. While New Westminster is at least blessed with ample SkyTrain access, Richmond can only now contemplate the effects that the new RAV line will have when rapid transit heads south from Vancouver over the Fraser River and up Number 3 Road. City of Richmond senior planner Suzanne Carter-Huffman says a 1995 city-centre area plan first sought the city core’s transformation from “very auto-oriented commercial and light industrial use to a fully functioning high-amenity, pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use downtown, and we’ve got 10 years under our belts of working with that.”

But RAV stations at Richmond Centre, Alderbridge and Cambie will boost development to the point that Richmond’s traditional car-oriented shopping centres, described by Carter-Huffman as “amorphous buildings floating in a sea of parking,” will have to adapt to higher density. She notes that this is already happening at the site of the Cambie station, where the newly revitalized Aberdeen Centre has a much higher density than its predecessor.

Even Richmond’s traditional street grid is being adapted to better reflect the needs of higher density. Citing Baron Haussmann, the 19th-century city planner who plowed major boulevards through the medieval streets of Paris, Carter-Huffman insists “the city doesn’t have that Haussmann approach to blasting new roads through downtown — it is done incrementally, as opportunities arise and development goes forward.”

A design feature unique to Richmond is readily apparent to anyone flying out of YVR who gazes down on the city’s small towers, restricted in height by airport flightpath requirements. Each building sits atop a podium, and each podium has a garden, putting green or other green amenity.

“With Richmond’s high water table,” Carter-Huffman explains, “parking is above grade and so we insist that all those podiums are landscaped. From the air the area is terrifically green.”

Richmond isn’t the only autooriented community to see development shifting toward the edge of the road and away from oceans of cars. The GVRD’s DeMarco notes that even in car-crazy Langley, single-family areas have been rezoned for higher densities.

“Most councils are afraid to do that,” she says.

In fact, it’s individual municipal councils that stand in the way of progress on one of the most egregious examples of sprawl faced by the region. Office parks are a boon for businesses seeking space at a far cheaper price than that paid in downtown Vancouver or regional town centres, and developers find them just as inexpensive to build. But they’re the bane of planners, who have a list of complaints about the sprawl of small buildings: They’re usually built far from transit, causing a kind of taxation on employees forced to maintain a car in order to commute, and are often deficient in retail outlets, restaurants and other public amenities.

“There’s no problem at all with industry going out to business parks where they need the space for manufacturing or distribution,” says DeMarco, “but offices that could locate in a centre and are choosing instead to locate in an out-of-centre location, that’s the planning challenge.”

She paraphrases the way that municipalities justify such development: “If we didn’t allow business parks then our neighbours would. We’ll lose the tax assessment, we’ll lose the jobs, and the region won’t be any better off.”

Cheeying Ho is executive director of Smart Growth B.C., which hosted the Financing Smart Growth forum on June 17.

“The GVRD is doing an okay job and its livable regions plan is a good plan,” Ho says, “but it needs to be updated, which they’re doing now. The problem is that it doesn’t have legislative power, it doesn’t have teeth, so it’s been challenged by municipalities >wanting to do their own thing. As a plan and policy it’s really good, but it needs to be enforced.”

Ho says business parks should be built as complete communities tied in to transit, with development cost charges changed to encourage sustainable development. Ironically, notes DeMarco, “some economists are saying that with our forecast labour shortages, employers have to be more careful about providing all the amenities they can to their employees.

That’s backed up in a 2004 report by commercial real-estate experts Avison Young, which warned that “these amenity requirements are increasingly pulling many tenants away from isolated business parks and toward downtown, town centres and other highly urban areas (such as West Broadway). Transit access is also a concern or even a requirement for many companies.”

The proof of the pudding is in the tasting, and no one is savouring a bigger banquet than North Vancouver Mayor Sharp. She says her municipality is enjoying a raft of benefits from paying close attention to development issues, as when the city reduced some road widths and sold the extra land to developers.

District energy

Then there’s the Lonsdale Energy Corporation, a district energy system installed in pipes as streets and sites were being torn up in lower Lonsdale. As the city describes it on its website, “the LEC district energy system produces hot water at a series of mini-plants within Lower Lonsdale and then distributes the hotwater energy through underground pipes to buildings connected to the system. Once energy is used in the connected buildings, the cooler water is returned to a mini-plant, reheated and circulated back to the connected buildings.” Five major buildings are now connected to the LEC district heating system.

Another success story has just started with the first stretch under construction along West Keith Road of what will be a seven-kilometre “green necklace” path for pedestrians, cyclists, in-line skaters and people in wheelchairs. It, too, was funded by the sale of some city land holdings.

Sharp says an odd problem the city has with its ambitious plans is the curse of NIMBY — the “not in my back yard” syndrome.

“There are people living along the route of the “green necklace” who say, ‘We don’t want all these people going by my house.’ But it’s everybody’s path! Those who take a leadership role in implementing these wonderful sustainable practices are vulnerable because of the groups that form that don’t want any change at all.”

There’s also opposition to allowing single-family homes to have secondary suites above a garage, dubbed coachhouse development.

“It’s a huge issue,” says Sharp, “with accusations that we’re destroying the single-family neighbourhood. There’s a lot of mistrust and resistance to change, but I think you can integrate them quite easily.”

Another NIMBY issue is noise.

“I think that some people going into condos come from singlefamily homes, and it’s not the same thing,” says Sharp.

“When you buy in the middle of the city, in a dense neighbourhood, you’re not buying in the country.”

[email protected]

North Vancouver City Mayor Barbara Sharp: ‘In order to be sustainable we’re going to have to try to learn to live together.‘ GLENN BAGLO / VANCOUVER SUN