To see mountain and sea from the glass home but not be seen is the challenge of downtown Vancouver residency

Christina Symons

Sun

Vancouver Sun readers received their first look inside an occupied Woodward’s apartment last month, courtesy of homeowner Fred Lee, a broadcaster and columnist. An openplan apartment like the Lee residence reflects household needs today, not the least of which is to make up for lost time by, for example, entertaining dinner guests while preparing dinner, says architect Michelle Biggar, a Woodward’s designer as a principal at Mcfarlane Green Biggar Architecture + Design. The bedroom, below, disappears and appears behind a sliding door. Photograph by: Ward Perrin, PNG, Special To The Sun

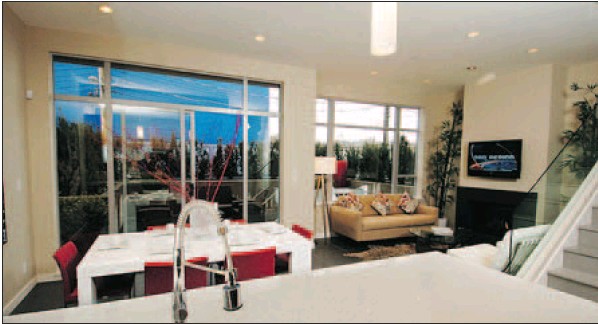

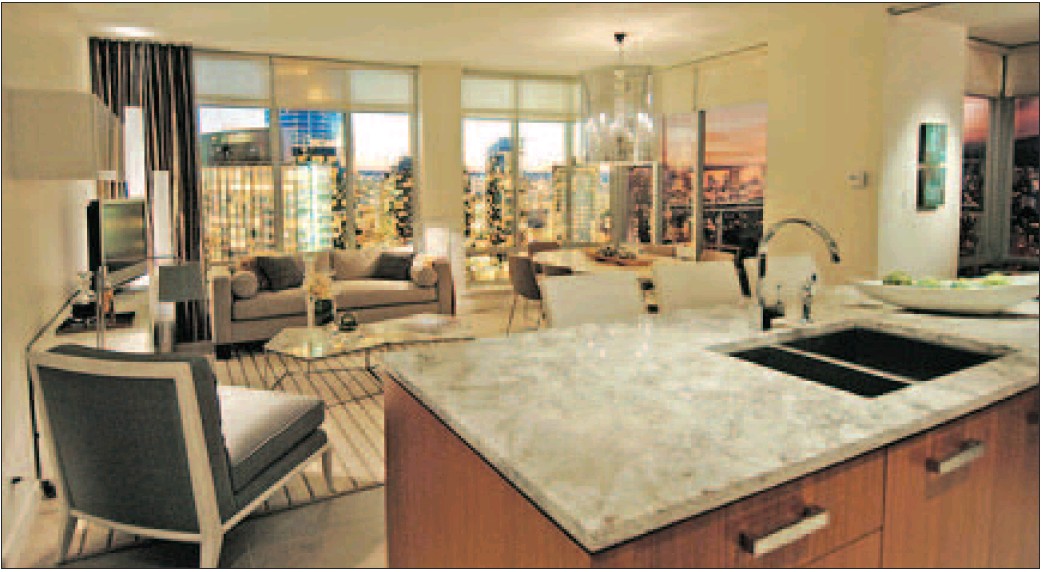

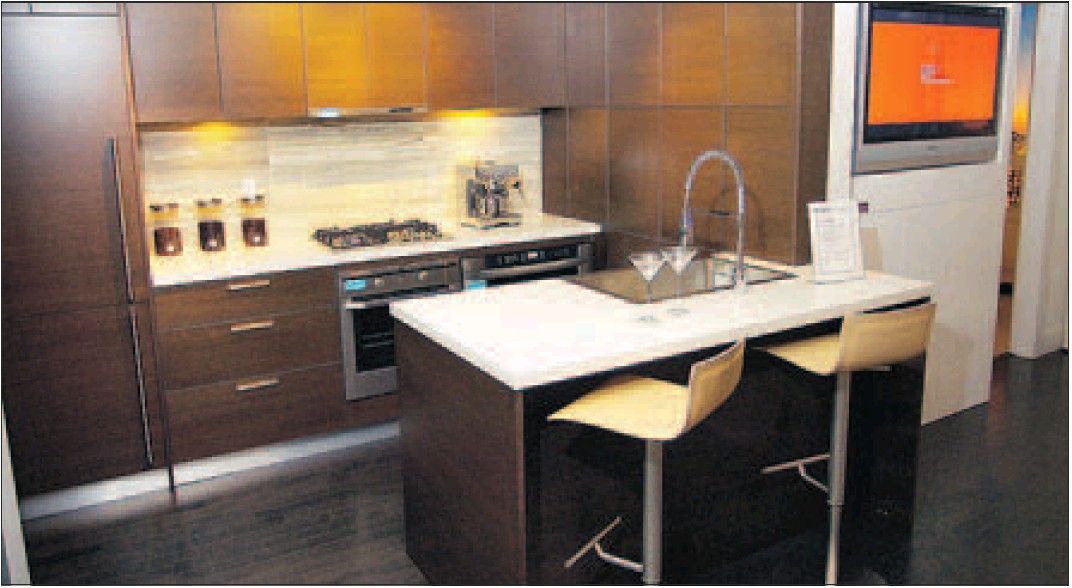

Dwellingson3rd is shown left and centre, Dolce is shown at the right.

While there’s some debate about the origins of open-plan interior design locally and about its eventual longevity, there’s no debating the domination of the interiors of most new homes locally by the open plan.

The re-imagining of downtown Vancouver as a residential neighbourhood, of attached homes, highrise and low-rise, and the re-imagining of the attached-home interior occurred more or less simultaneously, in the previous two decades

In that simultaneity is the possibility that the open -plan interior is as much an attribute of “Vancouverism” as are the more widely discussed attributes of the ideology, the creation of space between highrises, for example, with low-rises and public amenities.

Forty years ago, the new Vancouver apartment was inevitably a mini-maze house, with a proper hallway and kitchen and dining room and bedrooms.

Today, the new Vancouver apartment is inevitably without a formal entry and corridors and the traditionally enclosed kitchen. For the most part, the walls, and doors, are gone.

So smitten are so many of us with downtown residency, for its urbanity, for its environmental sensitivity, we’ll happily squeeze more into less, or more into more, as long our home has an entry with a view, with lots of floor-to-ceiling glass and minimal spatial restriction in between.

“It’s a trend that’s evolved predominantly as a lifestyle choice,” says architect Michelle Biggar, principal at Mcfarlane Green Biggar Architecture + Design, a multidisciplinary firm that has created some of Vancouver’s most progressive and high-end interior living spaces, including Woodward’s and select suites at The Estates, Fairmont Pacific Rim.

“An open plan reflects a modern lifestyle by encouraging interaction,” Biggar says, noting that most of us are ‘time poor’ these days and therefore value time with family and friends as paramount over private spaces. The open plan is conducive to modern mingling and attuned to living less rigidly.

Hosts are often preparing food while socializing with their guests either in their open-plan kitchen or at the barbecue, where the outdoors has become an extension of the interior living areas.

As Vancouver’s market demands increase and developable space detracts in unison, our living environments are again transforming. The benefits of radical open plan are being taxed as micro-living units are emerging.

Developers, designers and realtors are now taking a second look at the openplan concept and the smart ones are exploring solutions for existing environments while considering modifications for the next generation of “it” spaces.

Vancouver-based architect, planner and developer consultant Michael Geller, with four decades experience on key Vancouver landmarks such as the Bayshore, reconsiders the past.

Remember what proper houses were like 100 years ago, Geller notes. Every room had walls and a door, including the living room. To maximize modern spaces, Geller thinks we should reinstitute some of those ideas for select one-bedroom apartments in the city.

“The reason being is that as soon as you put a wall and door on the living room you can convert your one-bedroom apartment into a two-bedroom apartment, if you choose to,” he says. This idea was proven by Geller and the designers at the innovative UniverCity development at SFU. The open-plan kitchen and eating area essentially becomes the living space, while the enclosed former living room is seconded to a bedroom.

Often, we take all the walls out on the assumption that is more flexible, but we create more restrictions, Geller contends. For people who want to share, it doesn’t work and it also doesn’t work for households with children or for households with different lifestyles.

On the other hand, Geller admits that many traditionally enclosed or separated spaces such as formal dining rooms have proven to be completely redundant by today’s lifestyle standards.

He cites a talk by designer Gene Dreyfus of Childs-Dreyfus in Chicago who once calculated what a formal dining room costs us in terms of mortgage value. In Vancouver, that translates to approximately 150 square feet of dining space times an average value of $800 per square foot, or $120,000.

Over 20 years, it costs us around $1,500 each time we use our dining room (four times a year, for formal holiday dinners let’s say).

“For that price, you could rent a private dining room at a nice hotel and be further ahead,” says Geller.

Stephanie Corcoran, past president of the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, a realtor specializing in Vancouver living spaces on the west side, concurs. Corcoran’s been in the business since 1986, and recalls the birth of downtown open-plan living in Vancouver sometime in the ’90s -a design tenant that was, and is, about simple economics and buyer demands she says.

“Developers had to design and build highly efficient spaces, complete with all the bells and whistles,” Corcoran notes. “Visually, small spaces simply appeared lighter and brighter with an open plan.”

The first enclosed room to go was the kitchen, morphing to an open plan and liberating that space for all to mingle in.

Corcoran recalls potential buyers’ first reactions to the shift.

“Buyers were very worried that guests would see the mess!'” Corcoran notes.

At first, the market was very tentative, but eventually buyers embraced this new style of living and the rest is history, she says.

“We used to hide the kitchens,” says Geller, who witnessed the kitchen evolution in design terms over a few decades.

The first innovation was opening it up just a little bit, from a galley into what became known as a keyhole kitchen.

“At the time, during the ’70s you opened it up as much as possible in the existing space but you would never dream of really opening it up,” says Geller. Today, developers renovating those early ’70s and ’80s kitchen are busting out of the constraints, breaking down the walls to bring the living spaces up to date.

“The best party place in any home is a kitchen living hub,” says Corcoran. “Today’s small spaces are the norm and with the open plan the party happens around you.”

Of course, the Vancouver market is also fixated on “the big view”, says Biggar. Today, the all-glass towers that Vancouver is so well known for, along with an open-plan interior, allow this view to be uninterrupted throughout the suite.

“People in Vancouver want to enjoy the view from every square foot in their home including the bathroom,” laughs Geller.

But as empty nesters downsize and we make apartments smaller we can’t just shrink all of the spaces, says Geller. You have to rethink the layout and the way we utilize those spaces. You might covet all that glass and openness at first, but once you move in, but then need a bit of wall space -to hang artwork for example.

“I had dinner at a friend’s place recently and he had a very good oil painting that he wasn’t willing to part with so he has literally suspended it in front of a window,” Geller notes.

Other challenges include living with less clutter and mess as there is no place to hide it. Design and layout of furniture is critical and while family interaction is integral to open plan living, the need for everyday privacy can sometimes be a challenge.

Enter the sliding wall.

At Woodward’s, Biggar and her team utilized it creatively.

“We embraced open living not only in the kitchen, living and dining areas which were a combined space, but also in the bedrooms, many of which have large sliding walls to allow occupants to open the bedroom up to the living area to make it more spacious when not needed as a private area,” Biggar notes.

In addition, one neutral, timeless colour scheme was presented providing unity throughout the open space and allowing purchasers to add their own personality and style through furniture, art and accessories. Retractable doors were introduced to enclose compact office desks, allowing clutter to be concealed when needed.

Finally, circulation was considered to allow one bathroom to function both as an ensuite and powder room without requiring access through the private bedroom.

The use of sliding doors or retractable walls doesn’t necessarily give you acoustic privacy, but gives you visual privacy, Geller notes. Along with alcove spaces, sliders are a trend that has proven successful in places such as New York and Toronto and are now becoming popular in Vancouver too.

“Sliding glass walls create privacy in bedroom areas, bring in light to enlarge the visual space and can also be left open to actually enlarge the space,” says Corcoran, who just sold a loft east of Cambie an entry adjacent to an open bedroom.

“The division wall is a sliding glass panel, so when open you’re actually in the bedroom when you enter the suite but you can close it off and it just looks like a nice hallway when you come in,” Corcoran says.

With the rollout of micro suites on Vancouver’s horizon, the need for such flexibility in open-style planning is paramount. “I think the Vancouver market needs to be challenged in a few more areas in order to further enhance the efficiency and livability of the smaller condo trend,” says Biggar.

To be successful, micro suites will need careful lateral design thought to maximize every possible space, Biggar notes The perceived need for dens and en-suites may need to be reconsidered while clever storage ideas and multi-functional spaces and furniture also need to be featured.

Perhaps studying more enclosed boat interiors would be a good precedent Biggar and Geller contend.

From open plan to the open sea, it’s an idea that seems very Vancouver.

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun

For more information on lofts check out our Vancouver Lofts website.